Blog and news

The potential of Chatham Island peatlands

Just how much carbon could Chatham Island peatlands hold? Masters research has started exploring the capacity for carbon sequestration in these valuable ecosystems, and the potential for alternative income for landowners.

Chatham Island peat

Thirty centimeters of healthy peat looks like delicious, rich chocolate mudcake. It's moist and dense. However, eating this sample is not advised.

Peat is made up from layers and layers of historic plant matter. It accumulates in damp conditions over a long period of time, with low levels of oxygen slowing its decomposition dramatically - which is what gives it that dark, rich appearance. As this organic material compacts over time, it forms peatlands and bogs. These habitats are important for a range of species, both plant and animal, and provide important ecosystem services that contribute to a healthy environment.

What’s more, all those layers of carbon-rich plant matter store carbon that would otherwise be in our atmosphere.

That’s why a small group of researchers - including Masters student Rabia Sheikh from the Netherlands - found themselves kneeling in the damp to take core samples of precious soil in the remote Chatham Islands.

A dracophyllum and sporadanthus bog with macrolearia on the Southern Tablelands, Rēkohu/Wharekauri. Image: Peter de Lange.

Peatlands as a carbon sequester

Globally, peatlands store twice the amount of carbon that forests do. This potential has led to many countries including carbon credits from peatlands on the open carbon market. The United Kingdom’s voluntary Peatland Code is a good example.

Aotearoa has around 240,000ha of peatland, with the Chathams accounting for approximately 42,000ha. Over half of Rēkohu/Wharekauri is peat.

If New Zealand were to adopt a carbon credit system linked to peatlands, it could help protect these areas while providing landowners with a passive income from land that’s generally unproductive for agriculture. But before this can happen, scientific data is needed to understand how much carbon the country's peatlands can store.

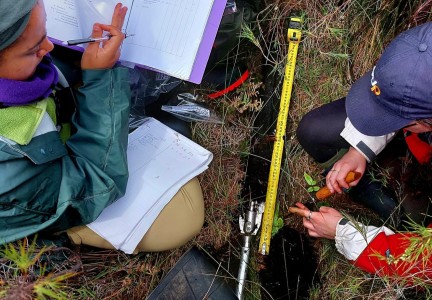

Kaeli Lalor and Rabia Sheikh peat core sampling.

Taking peat samples

Research to start quantifying carbon stocks in Chatham peatlands started in 2023 with a Masters research project by Rabia Sheikh (Radboud University, Netherlands). The research, completed in early 2024, was funded through the Essential Freshwater Fund and supported by Agri Concepts and the Nature Conservancy. Botanist Peter de Lange, Hamish Chisholm from the Chatham Islands Landscape Restoration Trust, Rob Chappell from the Chatham Island Conservation Board, and other landowners and conservationists also provided support.

An essential part of the research, Rabia explained to us, was comparing peatlands in different states: areas that had been drained or are currently being grazed by livestock, and areas that had been fenced to protect them and keep livestock off.

Seven sites that had different levels of protection were selected on main Chatham, and Rabia, with Peter and a small team, put on their gumboots and went into the field. They took samples by pushing a hollow tube known as a ‘core’ into the soil, then drawing it back out to provide a 30cm cylindrical section of peat.

Two core samples from Chatham wetlands; healthy on the left, and degraded on the right. Image: Peter de Lange

There were immediately noticeable differences.

In sites that had been protected, Rabia said the samples were compact and damp, and dark in colour - the mudcake effect. She could squeeze the soil and watch the water ooze out. In unprotected sites, the soil was lighter in colour, and so dry and brittle it crumbled in her hands - an indication of something awry in soil that's part of a 'wetland.'

“Some unprotected areas were too dry to use the core. We had to use a spade instead, because the core couldn’t go into the ground. In one area the core we took out was just beige clay, so we had to go to another area of the peatland to get a sample."

These samples are effectively cross-sections of what’s happening under the surface, with visible layers distinguishable by texture and colour. They can hold a lot about the history of an area, as well as its present state.

“A good indication of a peatland's current health is the active layer that shows up in a core sample,” Rabia said.

This active layer is where the process of forming peat is still underway, more fibrous than other layers while plants – commonly Dracophyllum scoparium and Sporadanthus traversii in Chatham peatlands – are decomposing. Effectively, Rabia said, it’s still forming and still going through the process of storing carbon.

One of the common peatland plants, Dracophyllum scoparium in flower. Image: Peter de Lange.

Quantifying the carbon

The chemical analysis of these samples was undertaken by Landcare Research, who quantified total organic carbon and nitrogen. Rabia said that initially, the results surprised her.

“The results showed that there was more carbon present in the samples from the unprotected peatland than the protected peatland. At a glance, this seems to be converse to what you’d expect."

However, this is put into context when considering the size of those active layers. The samples from protected sites had an active layer around 10-20cm thick, while unprotected sites had an active layer of no more than 5cm.

“This is because, with livestock there and trampling taking place, there’s no chance for the layer to form and grow over time.” The slow buildup and compression of plant matter that's characteristic of a healthy peatland can't happen as it would naturally, she explained.

“The results are due to the proportion of the active layer in a 30cm sample size. The thicker active layer has less carbon in it than the older layers. Those older layers are densely compressed, formed over decades and decades of plant matter decomposing, and they hold a lot more carbon.”

The larger active layers indicate the protected areas are forming new peat more quickly than the ones that aren’t protected. Because that active layer helps protect the older, carbon-rich layers beneath, it means layers under a thick active layer are less likely to be released into the atmosphere by disturbance.

Female sporadanthus traversii, a very unique Chatham Island peatland species. Image: Peter de Lange.

The potential of peatlands

This is just the very first step in understanding – and then using – the potential of peatlands in the Chathams.

More research is needed into how quickly a layer of peat forms in a specific peatland, Rabia said, although she mentioned that other research has indicated similarities between Waikato and the Chatham Islands when it comes to these accumulation rates. In Waikato, protected peatlands increase an average 1.9cm every year.

She also highlighted how relatively quickly peatlands can begin to recover with the right protections, and had a specific example from the Chatham Islands. After a local landowner decided to give up farming on an area of peat, within 15 years of keeping stock off the land they'd noticed a significant return of natural vegetation.

Funding is being sought to continue researching the function of these peatland ecosystems. This could allow them to explore opportunities for peatlands to be included on the open carbon market.

“People don’t realise how important peatlands are, and how much potential these wetlands have,” Rabia said.

Rabia Sheikh peat core sampling.

A personal note from Rabia

Rabia’s academic career started off with a course in the Netherlands, focused on nature in a crowded country. She learned about wetlands during this study, and ended up writing a paper on how New Zealand is tackling climate change. She was particularly interested in New Zealand’s focus on nature-based solutions.

From here, Rabia found out about the Nature Conservancy’s Blue Carbon project. This led to her doing her Master’s thesis in Aotearoa, with lots of support from the Nature Conservancy and her university in the Netherlands. She focused on the Chatham Islands, and carried out field work for the first time.

When asked what she liked most, she laughed and said, “What didn’t I like? The people are so welcoming and kind and generous. This island is so beautiful.” She enjoyed having conservations with the landowners, and appreciated how interested and curious people were about her work.

“It feels like you’re in the middle of the ocean, isolated, and there’s something so peaceful about that.” It’s an experience she’ll never forget.

Special thanks to all those mentioned in this blog, including Peter de Lange, Rob Chappell, Hamish Tuanui-Chisholm, as well as Kopinga Marae and Deb, Alfred Preece, Bruce and Liz Tuanui, Ruka Lanauze and Celine Gregory-Hunt, Tony Anderson, Milly Farquhar, Ruby Mulinder, and Olya from the Nature Conservancy.